Large families were common in the Baby Boomer era, and most kids in those days had plenty of siblings to play with, fight with, and to stick up for you. Henry and Evelyn Billion had one of those big Sioux Falls families, and their son Daniel, born in 1946, was a kid who benefited from a small army of sibling protectors.

Dan was the sixth of nine children, and his eldest sister Carolyn remembers when he was born. All was well at first, but he became sickly, and their mother said he became “orange as a copper penny.” This was before the days of bilirubin monitoring for newborn jaundice, a common condition. By the time a specialist was called in, though, brain damage had occurred, leaving him with cerebral palsy.

Dan came home and was lovingly cared for by his family, but it took longer to reach milestones—to hold up his head, to roll over, to sit up. He wasn’t expected to walk, but he did. “I remember holding his hand as he tried to learn to walk,” says his brother, Dave, who was closest to Danny in age. “I remember when he did take a step.” Danny was four when he achieved that goal. Their brother Jack (who passed away earlier this year) said Dan was a constant presence in the Billion family. He didn’t have the independence of other children, so he was “always there, with his kindness, his gentleness, his smile, his acceptance, and his courage.”

“Danny was our brother, and we took him everywhere with us,” says Carolyn. “We pulled him in a little red wagon. We taught the other kids on the block to accept him, OR ELSE. And this also worked out for other handicapped kids. Charlie on 4th Street had Down syndrome, and the kids at Terrace Park Pool made fun of him until we “educated” them. Our family passed out a few bloody noses now and then, but we always won. And so did those who taunted, they learned compassion and respect.”

Special education laws were decades away, so as the other children grew up and started school, Dan stayed behind. “In 1946, ‘crippled kids’ as they were called in those days, just stayed home,” says Carolyn. Henry and Evelyn wanted more for him, and worked hard to build an environment where Danny could develop his potential. They found a nurse/therapist named Virginia Skinner who was experienced in treating children with disabilities. They got together and bought a barracks at the Sioux Falls airbase, which had been vacated after World War II.

“They founded a parents’ group and encouraged them to bring their handicapped children to the air base facility, where they would try to help them in whatever way they could,” says Carolyn. “My mother took Danny out to the airbase every morning.” Sometimes the other children went along. Dave remembers going to the air base and playing with the kids there. Those early experiences had a deep impact. The need was great, and the school grew. Soon they needed a bigger facility.

In the meantime, waves of the polio virus were sweeping the country, striking mostly children and leaving them with various degrees of paralysis. The number of children with disabilities not attending school was growing, and public sentiment was demanding a change.

A grassroots group began the Crippled Children’s Hospital & School project in 1947, and Henry was named to the board in 1949 to help lead the effort. Land was purchased from “Robert Anderson and sons” on the edge of Sioux Falls for $4,500, and a groundbreaking event was held in October of 1950. “Crippled Children’s” opened in March of 1952, with Danny as one of the first students.

“As kids, we all walked to school in the old North End, but Dan didn’t get to come with us,” said Jack. “Mom would get him ready each day, and he’d get on that little yellow school bus and head off to the school called the Crippled Children’s Hospital & School, which should have been called The School for Brave Kids or The Unbelievable Effort School.” There, Dan continued his progress—learning to talk, moving one foot in front of the other in his walker, mastering activities like holding a spoon or drinking from an open glass. His siblings remember that he never complained and was never discouraged.

Dave says he and all of Danny’s siblings learned a lot of responsibility from their experience. “Danny took a lot of time, and our mother’s focus was on him,” says Dave. “It enabled us to pitch in–to learn how to take care of yourself and one another. We didn’t have all the outside activities that kids have now. Saturday was housework day—you changed the sheets on all the beds—that kind of thing. You had responsibility. You did the dishes because Mom was busy with Danny. You cooked the meals because Mom was busy with Danny.” Dave says there was no resentment; it’s just what you did. “It was good for everybody,” he says.

Carolyn became a volunteer and recruited her Junior Catholic Daughters group from Cathedral School to get involved, too. As high schoolers, the girls would help feed the children, write letters for them, read to them, take them for walks, and help with lessons. “We played what games they were able to play, and helped in whatever way we could,” says Carolyn. “For a time, Danny stayed at the school and came home on weekends.”

Dan graduated from Crippled Children’s and took some classes at Sioux Falls College, now the University of Sioux Falls. As an adult, he lived independently, but spent a lot of time with his parents, often riding his three-wheeled bike to their home for dinner and to watch Wheel of Fortune. He loved computers, crossword puzzles, chocolate milk, and people. Dan never spoke in anger, never held a grudge, and was never judgmental. He never excluded anyone.

Danny died suddenly on June 12th, 2008, at the age of 61. Jack noted in the eulogy he gave at Danny’s funeral that for once, Dan didn’t have to wait for his brothers and sisters. “He’s finally first, running on ahead. It’s a new experience and well-earned.”

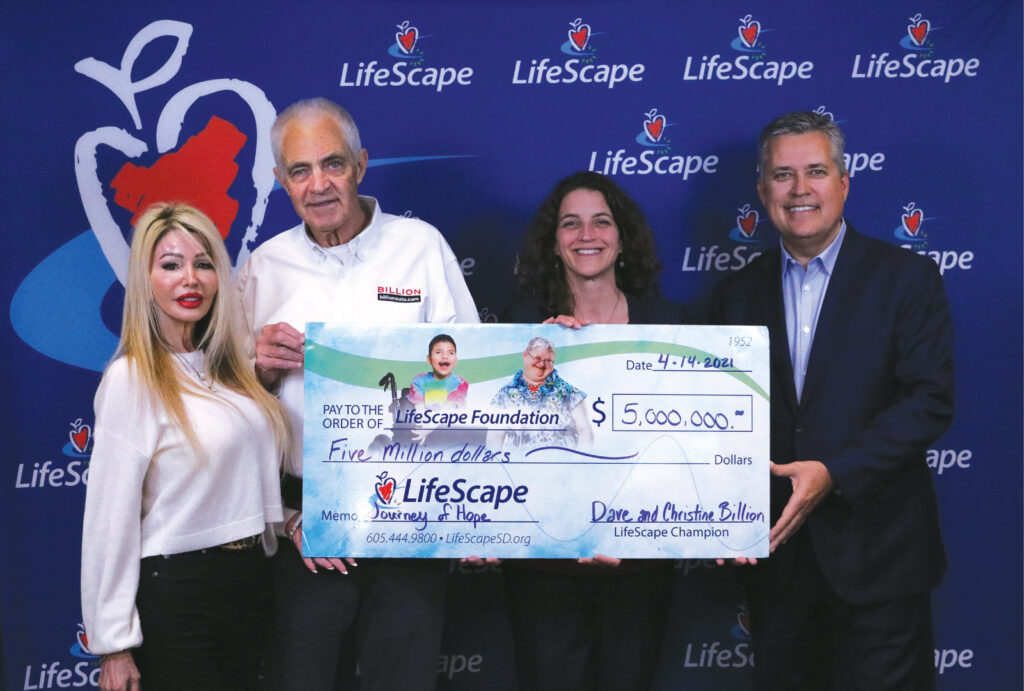

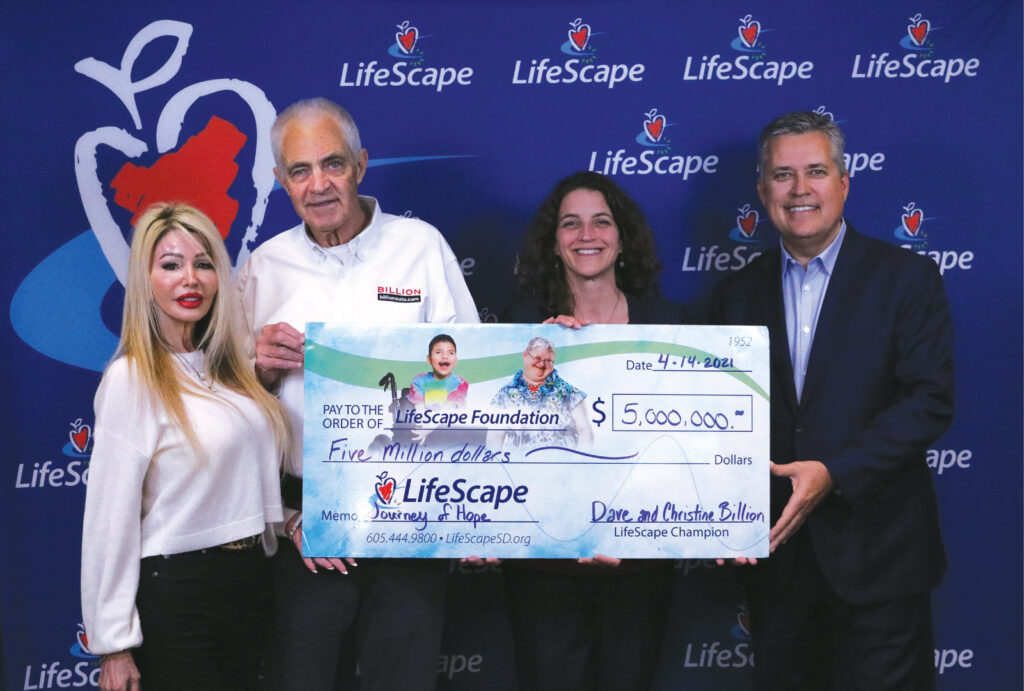

Now to thanks to Danny’s brother Dave and his wife Christine, the new LifeScape School will be named in honor of Danny and his parents. “I cannot adequately express the impact that having Danny as a brother had on my life,” says Dave. “Gratitude, compassion, concern, family, drive, and duty are words that come to mind. Danny was truly an inspiration and an example to all. We feel blessed to be participating in providing an entirely new campus for LifeScape. This modern facility will allow South Dakota and LifeScape to again become the leading model in the United States for assisting and educating those most in need.”

“You work to help other people; that was a lesson that was learned by having Danny as a brother,” says Dave. “You felt double the responsibility to live your life as best you can, because there are others that had their talents taken away from them out of no fault of their own. So, you need to use the gifts God has given you. It all stems from that.”

The Henry, Evelyn, & Danny Billion School at LifeScape honors the contributions of each. For Henry, who raised money, helped with the business plan, and personally recruited the first executive director, Dr. E.B. Morrison. For Evelyn, who made things happen rather than accepting the status quo, juggling the needs of a large family to be sure her son had a better chance at life. And for Danny, who inspired his parents to help establish the first school, and his brother to ensure a new school will be there for the future. Danny is again running on ahead, blazing the trail for those coming after him, and the new school will carry on the work.

Dan came home and was lovingly cared for by his family, but it took longer to reach milestones—to hold up his head, to roll over, to sit up. He wasn’t expected to walk, but he did. “I remember holding his hand as he tried to learn to walk,” says his brother, Dave, who was closest to Danny in age. “I remember when he did take a step.” Danny was four when he achieved that goal. Their brother Jack (who passed away earlier this year) said Dan was a constant presence in the Billion family. He didn’t have the independence of other children, so he was “always there, with his kindness, his gentleness, his smile, his acceptance, and his courage.”

“Danny was our brother, and we took him everywhere with us,” says Carolyn. “We pulled him in a little red wagon. We taught the other kids on the block to accept him, OR ELSE. And this also worked out for other handicapped kids. Charlie on 4th Street had Down syndrome, and the kids at Terrace Park Pool made fun of him until we “educated” them. Our family passed out a few bloody noses now and then, but we always won. And so did those who taunted, they learned compassion and respect.”

Special education laws were decades away, so as the other children grew up and started school, Dan stayed behind. “In 1946, ‘crippled kids’ as they were called in those days, just stayed home,” says Carolyn. Henry and Evelyn wanted more for him, and worked hard to build an environment where Danny could develop his potential. They found a nurse/therapist named Virginia Skinner who was experienced in treating children with disabilities. They got together and bought a barracks at the Sioux Falls airbase, which had been vacated after World War II.

“They founded a parents’ group and encouraged them to bring their handicapped children to the air base facility, where they would try to help them in whatever way they could,” says Carolyn. “My mother took Danny out to the airbase every morning.” Sometimes the other children went along. Dave remembers going to the air base and playing with the kids there. Those early experiences had a deep impact. The need was great, and the school grew. Soon they needed a bigger facility.

In the meantime, waves of the polio virus were sweeping the country, striking mostly children and leaving them with various degrees of paralysis. The number of children with disabilities not attending school was growing, and public sentiment was demanding a change.

A grassroots group began the Crippled Children’s Hospital & School project in 1947, and Henry was named to the board in 1949 to help lead the effort. Land was purchased from “Robert Anderson and sons” on the edge of Sioux Falls for $4,500, and a groundbreaking event was held in October of 1950. “Crippled Children’s” opened in March of 1952, with Danny as one of the first students.

“As kids, we all walked to school in the old North End, but Dan didn’t get to come with us,” said Jack. “Mom would get him ready each day, and he’d get on that little yellow school bus and head off to the school called the Crippled Children’s Hospital & School, which should have been called The School for Brave Kids or The Unbelievable Effort School.” There, Dan continued his progress—learning to talk, moving one foot in front of the other in his walker, mastering activities like holding a spoon or drinking from an open glass. His siblings remember that he never complained and was never discouraged.

Dave says he and all of Danny’s siblings learned a lot of responsibility from their experience. “Danny took a lot of time, and our mother’s focus was on him,” says Dave. “It enabled us to pitch in–to learn how to take care of yourself and one another. We didn’t have all the outside activities that kids have now. Saturday was housework day—you changed the sheets on all the beds—that kind of thing. You had responsibility. You did the dishes because Mom was busy with Danny. You cooked the meals because Mom was busy with Danny.” Dave says there was no resentment; it’s just what you did. “It was good for everybody,” he says.

Carolyn became a volunteer and recruited her Junior Catholic Daughters group from Cathedral School to get involved, too. As high schoolers, the girls would help feed the children, write letters for them, read to them, take them for walks, and help with lessons. “We played what games they were able to play, and helped in whatever way we could,” says Carolyn. “For a time, Danny stayed at the school and came home on weekends.”

Dan graduated from Crippled Children’s and took some classes at Sioux Falls College, now the University of Sioux Falls. As an adult, he lived independently, but spent a lot of time with his parents, often riding his three-wheeled bike to their home for dinner and to watch Wheel of Fortune. He loved computers, crossword puzzles, chocolate milk, and people. Dan never spoke in anger, never held a grudge, and was never judgmental. He never excluded anyone.

Danny died suddenly on June 12th, 2008, at the age of 61. Jack noted in the eulogy he gave at Danny’s funeral that for once, Dan didn’t have to wait for his brothers and sisters. “He’s finally first, running on ahead. It’s a new experience and well-earned.”

Now to thanks to Danny’s brother Dave and his wife Christine, the new LifeScape School will be named in honor of Danny and his parents. “I cannot adequately express the impact that having Danny as a brother had on my life,” says Dave. “Gratitude, compassion, concern, family, drive, and duty are words that come to mind. Danny was truly an inspiration and an example to all. We feel blessed to be participating in providing an entirely new campus for LifeScape. This modern facility will allow South Dakota and LifeScape to again become the leading model in the United States for assisting and educating those most in need.”

“You work to help other people; that was a lesson that was learned by having Danny as a brother,” says Dave. “You felt double the responsibility to live your life as best you can, because there are others that had their talents taken away from them out of no fault of their own. So, you need to use the gifts God has given you. It all stems from that.”

The Henry, Evelyn, & Danny Billion School at LifeScape honors the contributions of each. For Henry, who raised money, helped with the business plan, and personally recruited the first executive director, Dr. E.B. Morrison. For Evelyn, who made things happen rather than accepting the status quo, juggling the needs of a large family to be sure her son had a better chance at life. And for Danny, who inspired his parents to help establish the first school, and his brother to ensure a new school will be there for the future. Danny is again running on ahead, blazing the trail for those coming after him, and the new school will carry on the work.

Carl and Marietta Soukup’s story with LifeScape began with music. As a high school student just over the state line in St. Helena, Nebraska, Marietta Soukup took accordion lessons from Johnny Matuska, a well-known Yankton-area musician, teacher, and music store owner. Matuska brought his music students to Sioux Falls to play for the children at Crippled Children’s Hospital & School, an experience Marietta never forgot. She was impressed with the care the children received. “It left an indelible mark in my mind,” says Marietta.

Many years later, after moving to Sioux Falls, Carl’s business, Soukup Construction, did some work for the organization as part of one of the expansion projects.

As parents and grandparents, and with Marietta’s career as a music teacher, the Soukups recognized the need for a regional specialty center to empower children with disabilities. This came into greater focus when a grandchild was born with a rare genetic disorder that resulted in significant physical and intellectual challenges.

The Soukups’ compassion for children moved them to make a lead gift to LifeScape’s Journey of Hope for a new children’s campus. “We always felt like we wanted to give back,” says Carl. “And it’s with great appreciation that we do so.”

Carl noted that the children and staff have been in cramped quarters for a long time, and that there are more children awaiting care. “You’re making a good move here,” he says. “It’s a need that will never go away.”

Their son, Jay, serves on LifeScape’s Governing Board of Directors, so the family’s commitment to the organization’s mission goes deep. They are all excited about the project. “LifeScape will be able to provide for the needs of people now and in the future,” says Marietta. “I’m so excited to know it’s going to happen.”

As parents and grandparents, and with Marietta’s career as a music teacher, the Soukups recognized the need for a regional specialty center to empower children with disabilities. This came into greater focus when a grandchild was born with a rare genetic disorder that resulted in significant physical and intellectual challenges.

The Soukups’ compassion for children moved them to make a lead gift to LifeScape’s Journey of Hope for a new children’s campus. “We always felt like we wanted to give back,” says Carl. “And it’s with great appreciation that we do so.”

Carl noted that the children and staff have been in cramped quarters for a long time, and that there are more children awaiting care. “You’re making a good move here,” he says. “It’s a need that will never go away.”

Their son, Jay, serves on LifeScape’s Governing Board of Directors, so the family’s commitment to the organization’s mission goes deep. They are all excited about the project. “LifeScape will be able to provide for the needs of people now and in the future,” says Marietta. “I’m so excited to know it’s going to happen.”

Heidi Schultz has spent her career in non-profit work. She’s always known that’s not where you make the most money, but it IS where you can make the most impact. One of her early professional jobs was as Director of Development for LifeScape, then Children’s Care Hospital & School. “I’m pretty mission driven,” says Heidi. “I like to know the work I’m doing every day is truly helping someone or making the world a little better.” In her nearly ten years at LifeScape, she says she learned a lot from families who persevered, and from donors who wanted to leave a legacy that mattered.

Heidi’s children grew up while she was at LifeScape, and she says they had life-changing experiences, too. When her daughter, Maddie, began volunteering at age five with a little girl who was a patient in the specialty hospital, Heidi never foresaw them becoming like sisters. She also didn’t expect the two families to meld into an extended family. Heidi became like a second mom to the girl, and advocated for her when she entered public school. Maddie and her brother Alexander learned about ventilator care, therapies, assistive devices, and became godparents to the girl’s younger sibling. Now, twenty years later, the families remain in touch—even though the girl who brought them together has passed away.

Maddie’s experience at LifeScape led her to a career as a pediatric occupational therapist herself, a profession she practices with true passion. But above all, Heidi says her kids learned compassion at LifeScape. “They are so comfortable with all different kinds of people, whether it’s different abilities or different nationalities, race, ethnicity, whatever. I feel like it just made them very open and accepting.”

Heidi learned in her work how much impact one experience can have. She remembered one woman who made small gifts each year but didn’t really know much about LifeScape. Then she toured Children’s Services and wept at the level of needs the children had, and the caring attention and opportunities they were given. “I think she was from an era when people with disabilities were shut away, and she was just so emotional about how they were valued and loved,” says Heidi. Another memorable donor was a man who had visited one time as a college student to bring Christmas gifts. He told himself that if he ever had the opportunity, he’d help. And he did. After a successful out-of-state career in engineering, he moved back to South Dakota and started a fundraiser for LifeScape and provided for the organization in his estate plan. “You just never know what’s going to spark somebody to just get engaged with a mission,” says Heidi.

Heidi named LifeScape in her own estate plans long ago and made a gift for the new Children’s Services building. She has also returned to the organization as a member of the Foundation Board. She is now seeing the gifts of people she worked with having an impact at LifeScape. “It’s just really joyous to be at a board meeting and hear about gifts maturing; people I had known during their lifetime; it’s super fulfilling,” she says. Her hope for LifeScape into the future? “First, I really would love to see this new campus come to fruition, to replace that 1950’s building. But what I really hope is that LifeScape always stays true to their mission and continues to evolve to meet the needs of people with disabilities.”

Heidi has made an impact on LifeScape and the people it supports through her working life, her children’s lives, her board work, and through her gifts and legacy. Truly, a life that matters.

Maddie’s experience at LifeScape led her to a career as a pediatric occupational therapist herself, a profession she practices with true passion. But above all, Heidi says her kids learned compassion at LifeScape. “They are so comfortable with all different kinds of people, whether it’s different abilities or different nationalities, race, ethnicity, whatever. I feel like it just made them very open and accepting.”

Heidi learned in her work how much impact one experience can have. She remembered one woman who made small gifts each year but didn’t really know much about LifeScape. Then she toured Children’s Services and wept at the level of needs the children had, and the caring attention and opportunities they were given. “I think she was from an era when people with disabilities were shut away, and she was just so emotional about how they were valued and loved,” says Heidi. Another memorable donor was a man who had visited one time as a college student to bring Christmas gifts. He told himself that if he ever had the opportunity, he’d help. And he did. After a successful out-of-state career in engineering, he moved back to South Dakota and started a fundraiser for LifeScape and provided for the organization in his estate plan. “You just never know what’s going to spark somebody to just get engaged with a mission,” says Heidi.

Heidi named LifeScape in her own estate plans long ago and made a gift for the new Children’s Services building. She has also returned to the organization as a member of the Foundation Board. She is now seeing the gifts of people she worked with having an impact at LifeScape. “It’s just really joyous to be at a board meeting and hear about gifts maturing; people I had known during their lifetime; it’s super fulfilling,” she says. Her hope for LifeScape into the future? “First, I really would love to see this new campus come to fruition, to replace that 1950’s building. But what I really hope is that LifeScape always stays true to their mission and continues to evolve to meet the needs of people with disabilities.”

Heidi has made an impact on LifeScape and the people it supports through her working life, her children’s lives, her board work, and through her gifts and legacy. Truly, a life that matters.

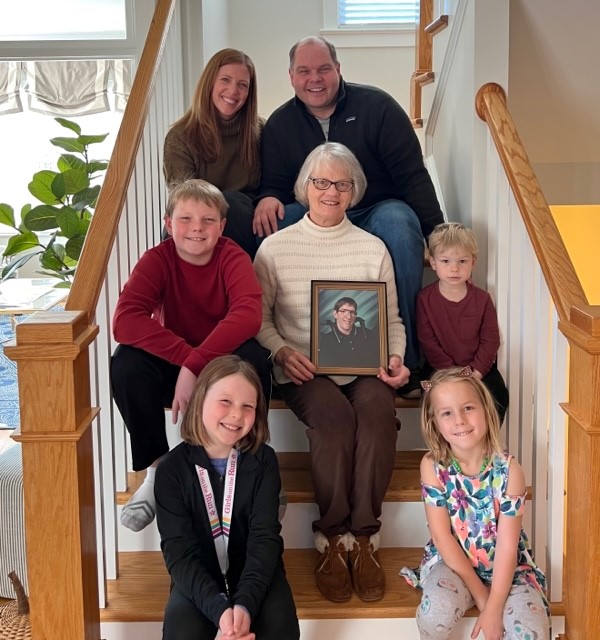

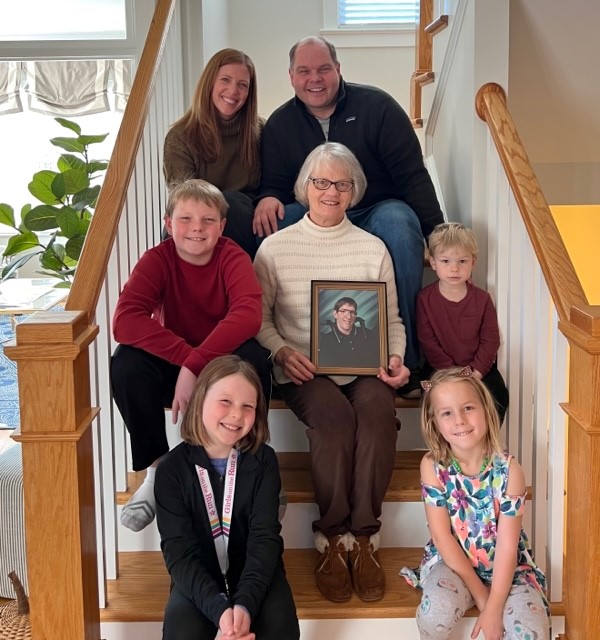

Robert Douglas Geyerman was born October 7, 1977, to Peter and Susan Geyerman of Watertown, SD. Complications during his birth left him without oxygen for a period of time, and he was later diagnosed with significant cerebral palsy. As he grew, his parents sought the best possible care for him. When Watertown started a special education program, Robbie was in the first group of students, but the Geyermans knew their son needed a higher level of services. That’s where LifeScape (then Crippled Children’s Hospital & School) came in. “We talked to United Cerebral Palsy in Des Plaines, IL,” says Susan. “They said you couldn’t do better than Crippled Children’s.” Although the prospect of their child being 100 miles away was difficult to accept, they knew he needed their specialized education and rehab services to have the best possible quality of life. In May 1982, when Robbie was four and a half years old, he enrolled in the residential and school program at LifeScape. On their first visit, they were relieved to find that Robbie was thriving, and they were delighted to see that everyone knew his name. Robbie was in good hands.

While the decision for residential care for Robbie was hard, a much bigger challenge was soon to come. Less than five months later, on October 1st, 1982, Peter was killed in a plane crash. Susan was now a single mother to Rob and his three-year-old brother Grant, with retail businesses in three cities. Susan says knowing that Robbie was safe and cared for was “a Godsend” as she worked through this tragedy.

The years went by, and Robbie continued to learn and grow. “Robbie enjoyed Crippled Children’s a lot,” says Susan. “It gave him friends, wonderful experiences, and education – more than he could have had anywhere else.” Robbie was student of the month, Valentine’s Day King, and in 1998, the honorary team captain for an SDSU vs. UC-Davis football game, sponsored by the Brookings Shrine Club. He graduated in 1999 and then was supported by an adult services organization in Sioux Falls.

After Robbie died in 2007, Susan began creating a legacy for both of them. She started making larger gifts to LifeScape and served nine years on the board of directors. For Susan, the most important thing is the future, and she has made a major gift to the new children’s facility. “I know the need,” says Susan. “It’s so important, not only for the person supported, but also for the whole family. It just saves the family. We have to keep LifeScape going for the people who need it now and into the future.”

The Geyermans benefited so much from the services at LifeScape, and now they’re paying it forward for future children like Robbie.

While the decision for residential care for Robbie was hard, a much bigger challenge was soon to come. Less than five months later, on October 1st, 1982, Peter was killed in a plane crash. Susan was now a single mother to Rob and his three-year-old brother Grant, with retail businesses in three cities. Susan says knowing that Robbie was safe and cared for was “a Godsend” as she worked through this tragedy.

The years went by, and Robbie continued to learn and grow. “Robbie enjoyed Crippled Children’s a lot,” says Susan. “It gave him friends, wonderful experiences, and education – more than he could have had anywhere else.” Robbie was student of the month, Valentine’s Day King, and in 1998, the honorary team captain for an SDSU vs. UC-Davis football game, sponsored by the Brookings Shrine Club. He graduated in 1999 and then was supported by an adult services organization in Sioux Falls.

After Robbie died in 2007, Susan began creating a legacy for both of them. She started making larger gifts to LifeScape and served nine years on the board of directors. For Susan, the most important thing is the future, and she has made a major gift to the new children’s facility. “I know the need,” says Susan. “It’s so important, not only for the person supported, but also for the whole family. It just saves the family. We have to keep LifeScape going for the people who need it now and into the future.”

The Geyermans benefited so much from the services at LifeScape, and now they’re paying it forward for future children like Robbie.

As the eldest of nine children growing up on a farm near Emery, SD, Mary Olinger learned how to work. So, when she retired in 2011 as the CEO of Make-A-Wish Foundation in Sioux Falls, she was ready for her next mission. “Once I retired, I had time, and I knew I wanted to put my time into something good,” Mary says. “I’ve always had a heart for kids and for people less fortunate than I.”

A friend, the late Cindy Walsh, invited her to join the Children’s Care Hospital & School Auxiliary, now the LifeScape Ambassadors. Mary jumped in with both feet, raising money, serving on committees, and lending her non-profit experience and wisdom to the group, of which she’s still a member.

The LifeScape mission was similar to that of Make-A-Wish, which grants wishes for children with critical illnesses. There Mary was constantly faced with the life and death situations of the children they served and the stresses on their families. It made her aware of the difficulties families face and sharpened her focus on serving others. Then a serious car accident nearly took her life, and her recovery has brought a deep sense of gratitude for life and its blessings.

Coming from such a large family, Mary has always had people around her, and she cares deeply about the well-being of all people. “I just think God put us here to serve, and that’s what I want to do – serve the people in the world that are less fortunate than I,” says Mary. “That’s my whole goal.”

In 2014, she joined the LifeScape Foundation Board of Directors. She served several years before taking a break and then returned this year for another term. “I enjoy the people and I like the progress and positive thinking,” says Mary about LifeScape. “I feel a comfort level—that this group of people really believes in the mission. They love the people they work with, and they know what they’re doing. It’s a well-oiled machine.”

When the Foundation Board began discussing a new LifeScape children’s facility, Mary was again all-in. “I’m a firm believer in having an up-to-date facility,” says Mary. She made a gift to the campaign, and says she wishes she could do more. Her dream is for LifeScape to have a facility and the staff needed to care for every person in South Dakota that has any kind of disability. She believes we all should have the chance to live our best life, and she’s ready to get going on that goal. “As I’ve said many times, let’s get it done!”

Coming from such a large family, Mary has always had people around her, and she cares deeply about the well-being of all people. “I just think God put us here to serve, and that’s what I want to do – serve the people in the world that are less fortunate than I,” says Mary. “That’s my whole goal.”

In 2014, she joined the LifeScape Foundation Board of Directors. She served several years before taking a break and then returned this year for another term. “I enjoy the people and I like the progress and positive thinking,” says Mary about LifeScape. “I feel a comfort level—that this group of people really believes in the mission. They love the people they work with, and they know what they’re doing. It’s a well-oiled machine.”

When the Foundation Board began discussing a new LifeScape children’s facility, Mary was again all-in. “I’m a firm believer in having an up-to-date facility,” says Mary. She made a gift to the campaign, and says she wishes she could do more. Her dream is for LifeScape to have a facility and the staff needed to care for every person in South Dakota that has any kind of disability. She believes we all should have the chance to live our best life, and she’s ready to get going on that goal. “As I’ve said many times, let’s get it done!”

Al Schoneman hadn’t planned to go into the building materials business his grandfather started in 1888 with his four brothers. When he left Washington High School in Sioux Falls to study business, economics, and political science at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, he was just searching for a career path.

Jobs were hard to come by in 1970 when he graduated, though, so he asked his dad Cecil Schoeneman if he could work “for a while” at Schoeneman Brothers Lumber, as it was then called. Cecil and his brother Herb were thrilled to have Al come back home to work in the family business, and hoped he’d stay, making it a third-generation enterprise. “And 54 years later, here we are,” says Al.

In May 2024, Schoeneman’s Building Materials Center was acquired by Texas-based Builders FirstSource, the nation’s largest building materials supplier. The name will remain with the four Schoeneman’s locations (Sioux Falls & Harrisburg, SD and Hawarden & Spencer, IA). Employee owners shared in the sale proceeds; another act of generosity arranged by Al.

“Generosity” is a big part of Al’s story, including with LifeScape, which he got connected to through family friend Bob Bennis. Bob was the co-founder of Ben Hur Ford and had a daughter with Down syndrome. He served on the board of Sioux Vocational Services, a forerunner of LifeScape, and encouraged Al to join the board, too. “I wasn’t on a board at that time, so it seemed like a good idea,” says Al. Plus, “Sioux Voc,” which served adults with disabilities, was right next door to his business.

He served from 1982 to 1998 on both the operations and foundation boards. There he saw the needs of people with disabilities and began his charitable giving to the organization.

“They’ve always done an excellent job of serving the clients,” says Al about LifeScape. “Unfortunately, the need doesn’t diminish, and the government just doesn’t provide enough financial support for them to live without charity.”

When Al was inducted into the South Dakota Hall of Fame in 2010, his biography listed his three-part motto: 1. Treat each customer the way that you would like to be treated. 2. Live a clean life and give back to your community. 3. Help young people achieve their goals, because helping young people is an investment in the future.

As a supporter of the LifeScape Journey of Hope, Al has invested in the future of children with disabilities, ensuring that kids for years to come will meet their highest potential.

“Generosity” is a big part of Al’s story, including with LifeScape, which he got connected to through family friend Bob Bennis. Bob was the co-founder of Ben Hur Ford and had a daughter with Down syndrome. He served on the board of Sioux Vocational Services, a forerunner of LifeScape, and encouraged Al to join the board, too. “I wasn’t on a board at that time, so it seemed like a good idea,” says Al. Plus, “Sioux Voc,” which served adults with disabilities, was right next door to his business.

He served from 1982 to 1998 on both the operations and foundation boards. There he saw the needs of people with disabilities and began his charitable giving to the organization.

“They’ve always done an excellent job of serving the clients,” says Al about LifeScape. “Unfortunately, the need doesn’t diminish, and the government just doesn’t provide enough financial support for them to live without charity.”

When Al was inducted into the South Dakota Hall of Fame in 2010, his biography listed his three-part motto: 1. Treat each customer the way that you would like to be treated. 2. Live a clean life and give back to your community. 3. Help young people achieve their goals, because helping young people is an investment in the future.

As a supporter of the LifeScape Journey of Hope, Al has invested in the future of children with disabilities, ensuring that kids for years to come will meet their highest potential.

Growing up in Sioux Falls, everyone was aware of “Crippled Children’s Hospital & School.” It was where the kids who had polio lived and went to school, because their home schools weren’t accessible for their crutches and wheelchairs.

I managed to dodge the polio epidemics of the late 40’s and early 50’s, and so did all of my friends. We were lucky—but for the kids who did get polio–Crippled Children’s made sure they were educated and got the best rehabilitation care available.

As an adult, I served on the investment committee for CCHS for about a dozen years. I was pleased to work on various community issues with Dr. E.B. “Jon” Morrison, who was the Executive Director from its opening in 1952 until 1984. E.B. was a passionate advocate for the children and helped craft South Dakota’s first special education laws. Through him, I got some insight into the great work being done there. I also became aware of how many kids were being treated and educated from all over the state and region. We were helping school districts from all over to fulfill their obligation to educate every kid. Arlene and I are making our gift in honor of Dr. Morrison.

I don’t remember CCHS opening in March 1952, but I’ve watched it evolve over the years. As central Sioux Falls residents for the past half century, my wife Arlene and I have driven past the children’s facility regularly and watched it evolve. We saw the building projects to expand the space as much as they possibly could. We saw the kids change—the disabilities became more significant, and many had multiple diagnoses and behavioral needs.

The current facility has been outdated and undersized for about a third of my life. Sioux Falls has done a great job meeting the needs of kids in every other area—educating and taking care of health needs–but kids with special needs are overdue for some attention and a new facility. What attracted us to the project is that the need is so clear.

The team at LifeScape has studied facilities all around the country. The new facility will allow them to adopt best practices that have been identified in this field. It will allow us to take better care of the growing population of kids with unique needs and multiple diagnoses than we’ve been able to do in an aging facility.

The first CCHS was built by concerned citizens across South Dakota and beyond. It’s time to do so again. If you haven’t already made a gift to the LifeScape Journey of Hope Capital Campaign for the new children’s facility, I invite you to join me in doing so. -Dan Kirby

I don’t remember CCHS opening in March 1952, but I’ve watched it evolve over the years. As central Sioux Falls residents for the past half century, my wife Arlene and I have driven past the children’s facility regularly and watched it evolve. We saw the building projects to expand the space as much as they possibly could. We saw the kids change—the disabilities became more significant, and many had multiple diagnoses and behavioral needs.

The current facility has been outdated and undersized for about a third of my life. Sioux Falls has done a great job meeting the needs of kids in every other area—educating and taking care of health needs–but kids with special needs are overdue for some attention and a new facility. What attracted us to the project is that the need is so clear.

The team at LifeScape has studied facilities all around the country. The new facility will allow them to adopt best practices that have been identified in this field. It will allow us to take better care of the growing population of kids with unique needs and multiple diagnoses than we’ve been able to do in an aging facility.

The first CCHS was built by concerned citizens across South Dakota and beyond. It’s time to do so again. If you haven’t already made a gift to the LifeScape Journey of Hope Capital Campaign for the new children’s facility, I invite you to join me in doing so. -Dan Kirby

Helen and Harold Boer know how important outdoor play is for kids – especially kids with disabilities. Their 12-year-old grandson, Ryan, born with a chromosomal disorder, can spend hours outside at their home near Lyons, SD, when he visits from Pennsylvania. His favorite thing is to be pulled behind the John Deere lawn tractor in a wagon, an activity which goes on as long as there’s gas in the tank and an adult willing to drive.

In Ryan’s honor, the Boers have made a $250,000 gift to LifeScape’s Journey of Hope, designated for the outdoor playground. “We know the need for these types of services,” says Harold.

Ryan is unable to speak or sing, but another of his great loves is music. He enjoys sitting with Helen when she plays piano and sings, but Katy Perry rules in his pop choices. So, it’s especially fitting that the playground section funded by the Boers includes musical play equipment. This will include giant chimes, a xylophone, and a mounted steel drum, plus a chalk art table.

The Boers are excited about the playground and the new children’s campus. They feel LifeScape would be the perfect school for Ryan if he lived in the area. “I hope he can visit and play there someday,” says Helen.

Ryan is unable to speak or sing, but another of his great loves is music. He enjoys sitting with Helen when she plays piano and sings, but Katy Perry rules in his pop choices. So, it’s especially fitting that the playground section funded by the Boers includes musical play equipment. This will include giant chimes, a xylophone, and a mounted steel drum, plus a chalk art table.

The Boers are excited about the playground and the new children’s campus. They feel LifeScape would be the perfect school for Ryan if he lived in the area. “I hope he can visit and play there someday,” says Helen.

The Billion School: Leading the Way

Carl & Marietta Soukup: “The need will never go away“

Heidi Schultz: Seeking a Life that Matters

Susan Geyerman: Paying it Forward

Mary Olinger: “Let’s get it done!”

Al Schoeneman – A profile in generosity

Dan & Arlene Kirby: Honoring the Legacy of Dr. E.B. Morrison

Helen & Harold Boer: A Gift in Honor of Their Grandson

Large families were common in the Baby Boomer era, and most kids in those days had plenty of siblings to play with, fight with, and to stick up for you. Henry and Evelyn Billion had one of those big Sioux Falls families, and their son Daniel, born in 1946, was a kid who benefited from a small army of sibling protectors.

Dan was the sixth of nine children, and his eldest sister Carolyn remembers when he was born. All was well at first, but he became sickly, and their mother said he became “orange as a copper penny.” This was before the days of bilirubin monitoring for newborn jaundice, a common condition. By the time a specialist was called in, though, brain damage had occurred, leaving him with cerebral palsy.

Carl and Marietta Soukup’s story with LifeScape began with music. As a high school student just over the state line in St. Helena, Nebraska, Marietta Soukup took accordion lessons from Johnny Matuska, a well-known Yankton-area musician, teacher, and music store owner. Matuska brought his music students to Sioux Falls to play for the children at Crippled Children’s Hospital & School, an experience Marietta never forgot. She was impressed with the care the children received. “It left an indelible mark in my mind,” says Marietta.

Many years later, after moving to Sioux Falls, Carl’s business, Soukup Construction, did some work for the organization as part of one of the expansion projects.

Heidi Schultz has spent her career in non-profit work. She’s always known that’s not where you make the most money, but it IS where you can make the most impact. One of her early professional jobs was as Director of Development for LifeScape, then Children’s Care Hospital & School. “I’m pretty mission driven,” says Heidi. “I like to know the work I’m doing every day is truly helping someone or making the world a little better.” In her nearly ten years at LifeScape, she says she learned a lot from families who persevered, and from donors who wanted to leave a legacy that mattered.

Heidi’s children grew up while she was at LifeScape, and she says they had life-changing experiences, too. When her daughter, Maddie, began volunteering at age five with a little girl who was a patient in the specialty hospital, Heidi never foresaw them becoming like sisters. She also didn’t expect the two families to meld into an extended family. Heidi became like a second mom to the girl, and advocated for her when she entered public school. Maddie and her brother Alexander learned about ventilator care, therapies, assistive devices, and became godparents to the girl’s younger sibling. Now, twenty years later, the families remain in touch—even though the girl who brought them together has passed away.

Robert Douglas Geyerman was born October 7, 1977, to Peter and Susan Geyerman of Watertown, SD. Complications during his birth left him without oxygen for a period of time, and he was later diagnosed with significant cerebral palsy. As he grew, his parents sought the best possible care for him. When Watertown started a special education program, Robbie was in the first group of students, but the Geyermans knew their son needed a higher level of services. That’s where LifeScape (then Crippled Children’s Hospital & School) came in. “We talked to United Cerebral Palsy in Des Plaines, IL,” says Susan. “They said you couldn’t do better than Crippled Children’s.” Although the prospect of their child being 100 miles away was difficult to accept, they knew he needed their specialized education and rehab services to have the best possible quality of life. In May 1982, when Robbie was four and a half years old, he enrolled in the residential and school program at LifeScape. On their first visit, they were relieved to find that Robbie was thriving, and they were delighted to see that everyone knew his name. Robbie was in good hands.

As the eldest of nine children growing up on a farm near Emery, SD, Mary Olinger learned how to work. So, when she retired in 2011 as the CEO of Make-A-Wish Foundation in Sioux Falls, she was ready for her next mission. “Once I retired, I had time, and I knew I wanted to put my time into something good,” Mary says. “I’ve always had a heart for kids and for people less fortunate than I.”

A friend, the late Cindy Walsh, invited her to join the Children’s Care Hospital & School Auxiliary, now the LifeScape Ambassadors. Mary jumped in with both feet, raising money, serving on committees, and lending her non-profit experience and wisdom to the group, of which she’s still a member.

The LifeScape mission was similar to that of Make-A-Wish, which grants wishes for children with critical illnesses. There Mary was constantly faced with the life and death situations of the children they served and the stresses on their families. It made her aware of the difficulties families face and sharpened her focus on serving others. Then a serious car accident nearly took her life, and her recovery has brought a deep sense of gratitude for life and its blessings.

Al Schoneman hadn’t planned to go into the building materials business his grandfather started in 1888 with his four brothers. When he left Washington High School in Sioux Falls to study business, economics, and political science at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, he was just searching for a career path.

Jobs were hard to come by in 1970 when he graduated, though, so he asked his dad Cecil Schoeneman if he could work “for a while” at Schoeneman Brothers Lumber, as it was then called. Cecil and his brother Herb were thrilled to have Al come back home to work in the family business, and hoped he’d stay, making it a third-generation enterprise. “And 54 years later, here we are,” says Al.

In May 2024, Schoeneman’s Building Materials Center was acquired by Texas-based Builders FirstSource, the nation’s largest building materials supplier. The name will remain with the four Schoeneman’s locations (Sioux Falls & Harrisburg, SD and Hawarden & Spencer, IA). Employee owners shared in the sale proceeds; another act of generosity arranged by Al.

Growing up in Sioux Falls, everyone was aware of “Crippled Children’s Hospital & School.” It was where the kids who had polio lived and went to school, because their home schools weren’t accessible for their crutches and wheelchairs.

I managed to dodge the polio epidemics of the late 40’s and early 50’s, and so did all of my friends. We were lucky—but for the kids who did get polio–Crippled Children’s made sure they were educated and got the best rehabilitation care available.

As an adult, I served on the investment committee for CCHS for about a dozen years. I was pleased to work on various community issues with Dr. E.B. “Jon” Morrison, who was the Executive Director from its opening in 1952 until 1984. E.B. was a passionate advocate for the children and helped craft South Dakota’s first special education laws. Through him, I got some insight into the great work being done there. I also became aware of how many kids were being treated and educated from all over the state and region. We were helping school districts from all over to fulfill their obligation to educate every kid. Arlene and I are making our gift in honor of Dr. Morrison.

Helen and Harold Boer know how important outdoor play is for kids – especially kids with disabilities. Their 12-year-old grandson, Ryan, born with a chromosomal disorder, can spend hours outside at their home near Lyons, SD, when he visits from Pennsylvania. His favorite thing is to be pulled behind the John Deere lawn tractor in a wagon, an activity which goes on as long as there’s gas in the tank and an adult willing to drive.

In Ryan’s honor, the Boers have made a $250,000 gift to LifeScape’s Journey of Hope, designated for the outdoor playground. “We know the need for these types of services,” says Harold.